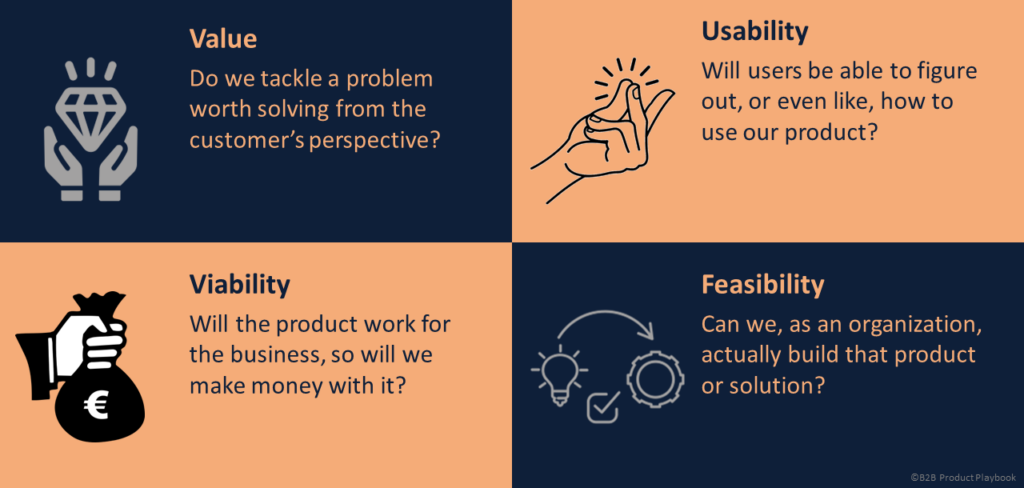

The Four Key Risks

Product Discovery, as will be explained in depth in Part 3 of this book, is needed to address four types of critical risks associated with product development. While there is no absolute guarantee of success, the objective is to collect enough confidence that a solution to be developed later during Product Delivery will actually solve the customer’s problem. These 4 key risks are:

Value Risk

Example

Fast food company Burger King in 2013 introduced Satisfries and advertised it as a healthier alternative to traditional french fries. The new fries were also more expensive than regular ones. In the end, the product was a failure and quickly discontinued, because consumers did not see any value in it.

Usability Risk

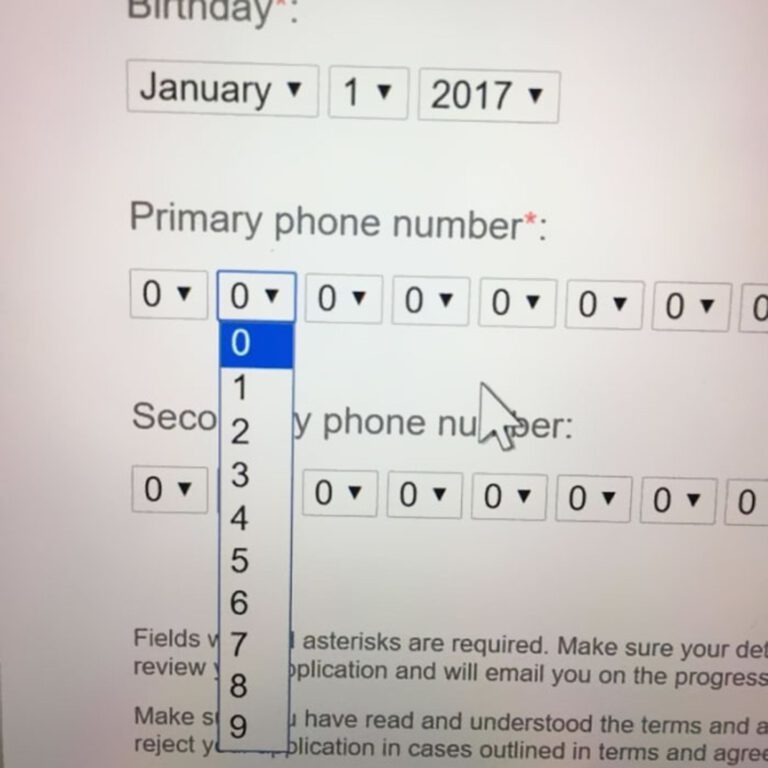

- Effectiveness: Does the product allow users to achieve their goals?

- Efficiency: Can users accomplish their goals with a minimum amount of resources, so quickly?

- Engaging: Is the product pleasant and satisfying to use?

- Error Tolerance: Does the product prevent errors caused by the user’s interaction and does it help recover from any errors that might occur?

- Easy to learn: Can the product be used with prior knowledge of users, does it apply patterns of interaction well-known to the target audience, is it predictable, can users extend their knowledge and skills easily?

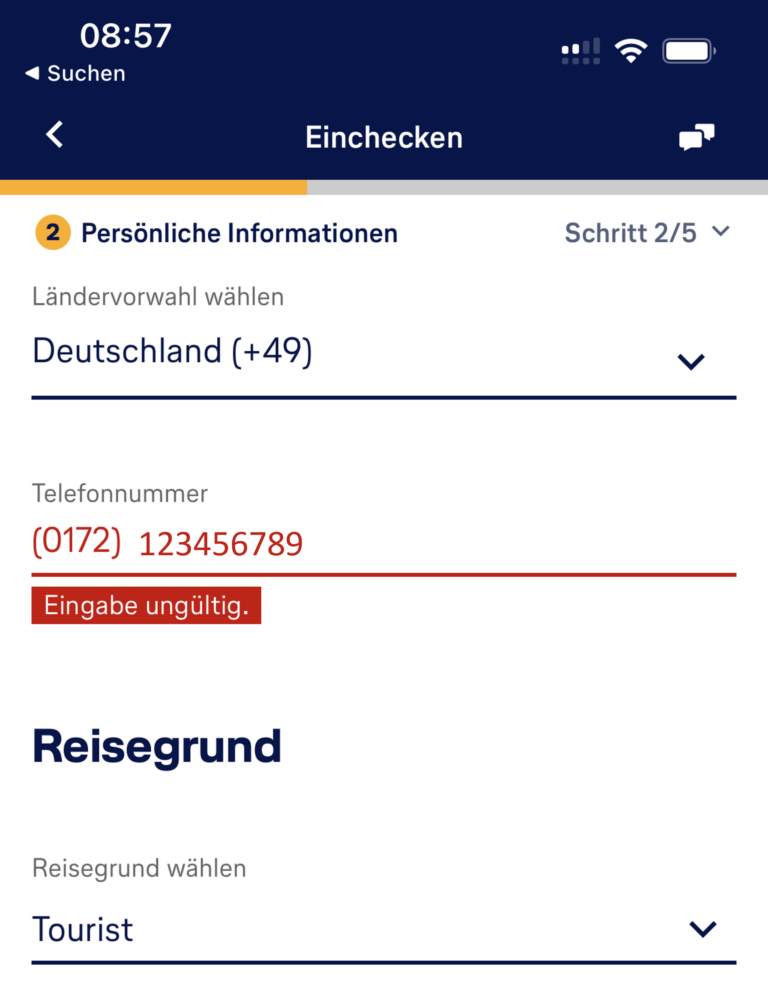

Obviously, the first one is a very clunky way of entering a phone number; but even the second form is falling short as it only complains about an invalid format — without any guidance as to which format is accepted.

To assess usability, it is crucial to have the specific target group in mind, the personas who are supposed to actually be using the product. Because their skills, their experience may differ from other groups of people just as the context of product utilization might be specific. As an example consider office environments, with stationary PCs on desks, and compare these to the factory floor and harsh environments, potentially even with sparse Internet connectivity. Skills and expectations of users will be very different in both environments, as is the context of using a tool.

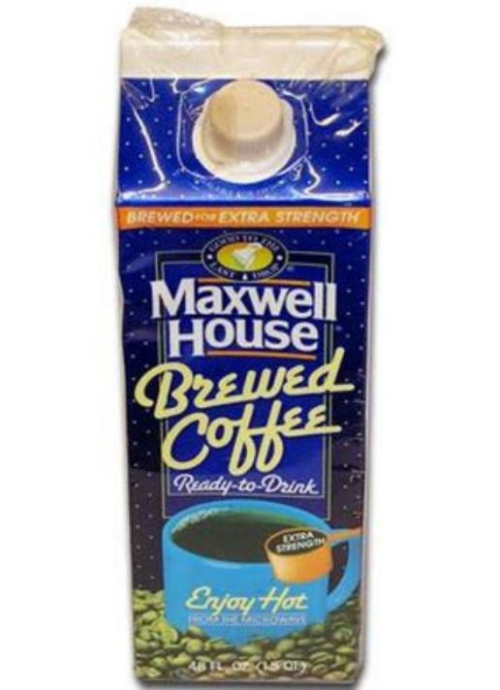

Example

Maxwell House Brewed Coffee was ready-to-drink, pre-brewed cold coffee, sold in a carton. Promising superior convenience to consumers, also with the picture of a hot mug on the packaging, it was in fact the opposite: hard to handle, and due to the packaging couldn’t be microwaved. The coffee was discontinued shortly after the release for poor usability.

Feasibility Risk

- Does the team know how to build, do they have the right skills and tools, did they even build something similar before?

- Will the team have the resources to build, most notably enough time?

- Are there any impacts on architecture, new components needed, or specific dependencies that need to be managed?

- Can the product be built to comply with SLAs, so be scalable and performant enough?

- Apart from building, can the team also roll out, configure and operate the product?

Example

In 1995 Microsoft released Microsoft Bob as a simple and easy-to-use interface. However, Bob did hardly work on standard hardware at that time and, instead, required way more processing power than standard home computers had at that time. Apart from other aspects, such as pricing and conflict with later Windows 95, the tool simply wasn’t feasible based on existing technology.

In most cases, feasibility will not be a major problem, specifically when it comes to more incremental feature development rather than inventing a brand-new product. The engineering team may have seen similar requirements many times before and, thus, quickly be able to eliminate concerns. In some situations, however, they might need a few days to investigate or even prototype in order to gain confidence or find a working solution.

Viability Risk

Looking at

As Product Managers, our job is to build products that our customers love, yet work for our business.

Marty Cagan

Example

Netflix, today known as the media streaming giant and producer of content, initially started as a deliver-by-mail DVD rental service competing with Blockbuster. To focus on online streaming, the company in 2011 announced Qwikster as a separate company handling the DVD business. The change also would have been much more expensive to customers wanting to consume both, DVD and streaming content. Being widely criticized, then plan was scrapped very soon as it would have hurt the overall Netflix business.

To summarize, even when we can build a new product, when usability would be great and there is no technical risk of building it — viability is about the question: Should we build this?

Note that this chapter did not address risks related to poor execution and failures in Product Delivery.

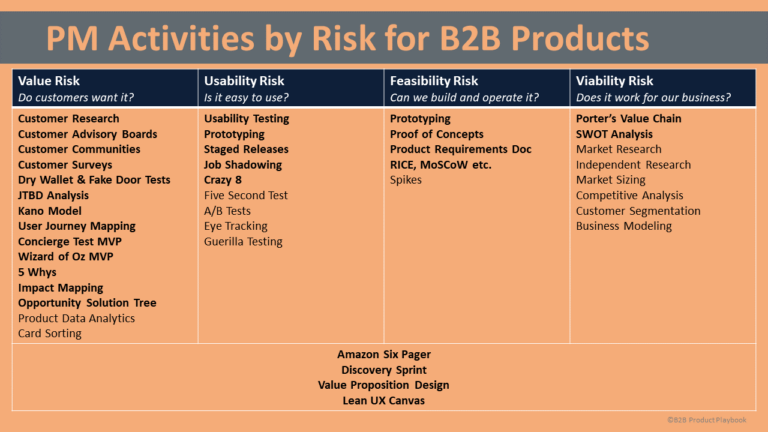

Tools to Mitigate the Risks

Some tools are specific for a particular risk while others can be applied more holistically. The entries marked in bold are explained in more detail in the Resources section of this playbook, and others are explained in the respective chapters describing our process.